The research results were presented by László Kökény, research author of the Climate & Energy Advisory of Századvég, followed by the reflection of three guest speakers

- Anna Iara, Policy officer, European Commission, Directorate-General for Climate Action – Governance and Effort Sharing;

- Ilona Vári, Head of EU Regulatory Affairs at MOL Group; and

- Ambassador Csaba Kőrösi, Director at the Office of the President of Hungary.

Take-away of the event

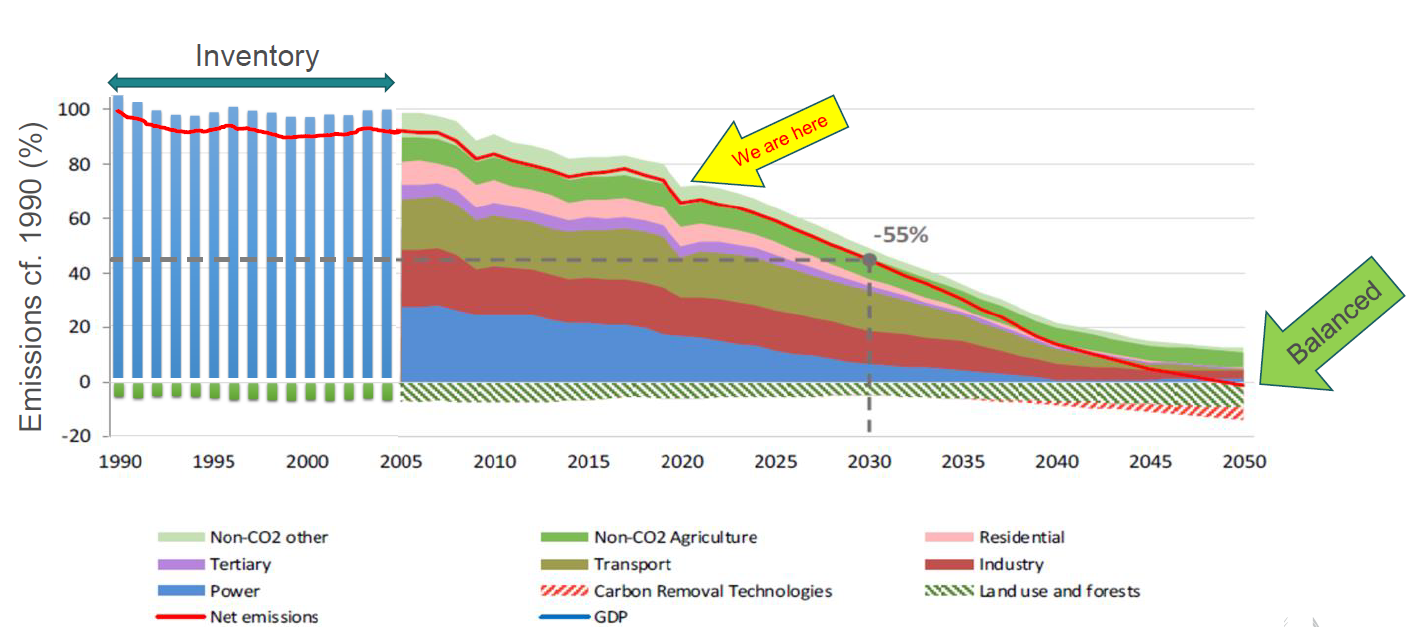

- The European Union set up its so-called zero-emission policy for 2050, which means that in 30 years the amount of carbon emission and the available processing capacity should at least be equal. This also means more ambitious progressive goals on the road to 2050, with stringent targets by 2030.

- MOL’s calculation concluded that every fifth Forint of the Hungarian state’s and companies’ spending should be invested in the energy transition in the next 45 years.

- Technological revolution and behavioural change is indispensable in most countries to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Mr. László Kökény presented the research conducted using CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing) method on 1049 companies, of which 42 entities operate under the ETS (Emission Trading System) while 1007 were selected from a representative sample of non-ETS, i.e. “low-emission” companies.

Companies have a positive attitude towards the state directives defining the process, two-thirds are indeed aware of them; companies with higher sales volumes and more employees consider the listed state guidelines as ‘strict but effective’. Also, it turned out, that more than 45% of Hungarian companies regularly follow international news and regulatory reports on the topic. However, the companies are no more ambitious than the directives expect them to be as regards the climate protection targets by 2030.

At the same time, companies consider the use of renewable energy sources to be the most important tool for achieving the climate protection goals. The below figure shows, that the current investments are mainly put in place by the “large emitters”, whereas more than 60-75% of the companies plan related developments by 2030.

The perception of the most important tools to achieve the climate goals though varies by companies, where a difference is visible between the small and the large emitters: while the development of renewable energy sources is the priority of non-ETS companies, the development of energy efficiency is considered as the most important tool by ETS companies. Two-thirds of the companies surveyed plan to install renewable energy sources, mainly PV and solar panels, already in the short term (within 5 to 10 years). Within energy efficiency investments, most companies consider building modernisation to be an effective tool, within which more than 70% of the companies consider the modernisation of heating systems as the primary element to be developed, followed by the replacement of machines and windows. Currently 30% of the companies plan to replace their fleet with electric vehicles within the next 15 years.

When asked which stakeholder group has the largest influence on the companies’ motivation for the Green Deal, the primary answer was: the customers – meaning,

if pressure from the customers grow, the companies might well consider to alter their current related behaviour.

Within this it can be concluded, that the smaller companies rather look at actors in their immediate environment (i.e. customers, competitors), while larger companies focus more on impulses coming from national bodies (regulators, service providers, public institutions).

In the course of achieving the targets, the survey showed that companies expect targeted state support and incentives in the form of multiple instruments (i.e. subsidies, specific calls, tax breaks), but are open to such opportunities not only as regards to energy efficiency and machine development investments, but also to education initiatives, targeted at their employees.

Ms. Anna Iara from the European Commission highlighted the regulatory framework, which is in the midst of a change and is expected to have a large influence on the stakeholders’ ambitions.

To achieve the climate neutrality goal (i.e. net zero green-house gas emission) scheduled for 2050, the reduction goals scheduled for 2030 were raised to 55% of the emission levels present in 1990, proposed a legislative package amending numerous existing legislations (i.e. ‘Fit for 55’). The approach combines different instruments: pricing (i.e. European emission trading system), targets (i.e. 55%) and rules.

There are three basic pillars of the climate policy architecture of the Union to support these goals:

- The first pillar is the current emissions trading system (ETS): a carbon trade system for CO2 emission allowances, traded on one market – this affects the energy sector (large industry emitters) and aviation, with the maritime transport proposed to be included in the system.

- The second pillar is based on the effort-sharing sectors, where there is no market for allowances, but the public sector / Member States are expected to act to reach lower emissions, breaking down the goals to national binding targets. These affected sectors are road transportation, buildings, agriculture, waste, small industry and F-gases, energy non-CO2, and other transport.

- The third pillar is the Land-Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) sector, where besides emission, carbon absorption capacity is present which will play a key role in achieving the net zero goals.

The planned transition is demanding: therefore 30% of the 2021-27 EU budget of two trillion euro are earmarked for climate action.

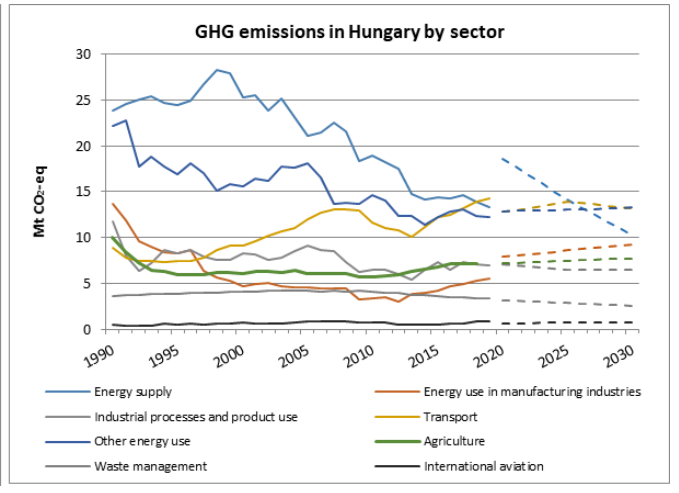

The Hungarian greenhouse gas emission and targets show a huge decline in the Energy sector, but there is an increase visible in the transportation sector, where action is considered necessary.

Ms. Ilona Vári said that climate change and decarbonisation are very important topics for MOL – one of the largest Hungarian companies – as well, therefore they closely follow the global European and national developments in the topic. The challenging goals of the Fit for 55 package seem to be achievable, however, the debates bring out many questions on decarbonisation – i.e. What is the timing? What are the costs? Who will pay for the costs?

MOL started its journey to put the company on a sustainable path in 2016. Previous measures of ‘energy efficiency’ were already then considered as insufficient, therefore MOL launched its strategy transforming the company to be fit for the low-carbon, “Beyond the fuel age”, where MOL becomes a chemical and mobility service company. The growing public demand and political will to intensify the decarbonisation process however, led MOL to launch its “Shape tomorrow” strategy in February 2021 8 which, due to the ‘Fit for 55’ package already needs to be revised), setting for the company carbon reduction targets and aiming to make the new solutions and technologies profitable for the company – due to market demand or regulatory support. In the course of the strategy formulation MOL identified plenty of new and available technologies, that can reduce greenhouse gas emission, occurring in different operations or production, and also big opportunities in electrification – the required electricity coming from renewable and low-carbon sources. MOL concludes that energy transition will only take place if there is appropriate and predictable regulation in place, promoting low carbon investments and low carbon solutions.

The company will reduce its group level Scope 1+2 emissions by 30% by 2030 and achieve net zero operation by 2050.

Besides the plan to increase investments in the low carbon future, the company also introduced some internal administrative measures to incentivise the management to reduce GHG emission of the company.

In MOL’s calculation, however, energy transition has a very high cost:

every fifth Hungarian forint of the state and companies’ spending would need to be invested in the energy transition during the next 25 years.

They also expect the transition to have effects on the public as well, i.e. through rising household energy costs and an increase in fossil fuel prices. Therefore, MOL believes in a clever, well-defined and well-timed regulatory approach that is needed to keep the consumers and stakeholders approve the climate change mitigation process and to uphold their support for the process.

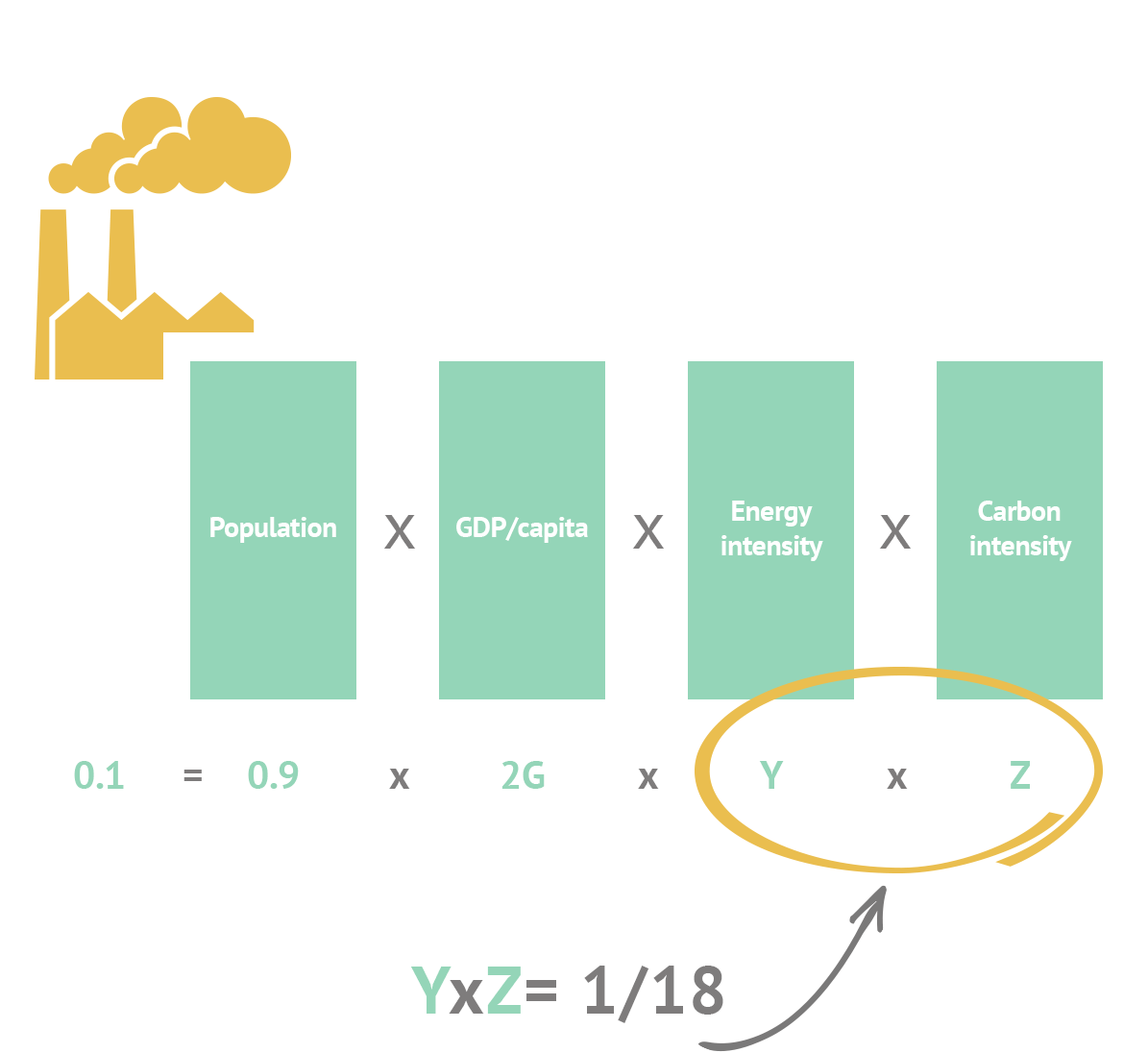

Ambassador Csaba Kőrösi, Director at Office of the President of Hungary gave a cross-cutting snapshot on achieving the emission goals on a national level. Carbon neutrality can be reached through emission reduction, which is defined by four factors: the size of the population; the GDP per capita; energy intensity and carbon intensity, primarily in the energy sector. These factors can be considered as multipliers – looking at the equation from this perspective, it is understandable, that the latter two factors are with which a country can currently deal with, which can therefore be considered as primary aims to achieve the goals. (The below table shows the formula with the expected parameters Hungary.)

To reach the carbon neutrality goals, a country would have generally two other opportunities (decreasing energy intensity is unlikely): increasing its carbon dioxide absorption or exporting its carbon-intensive activities – although the second option would not help the climate holistically at all.

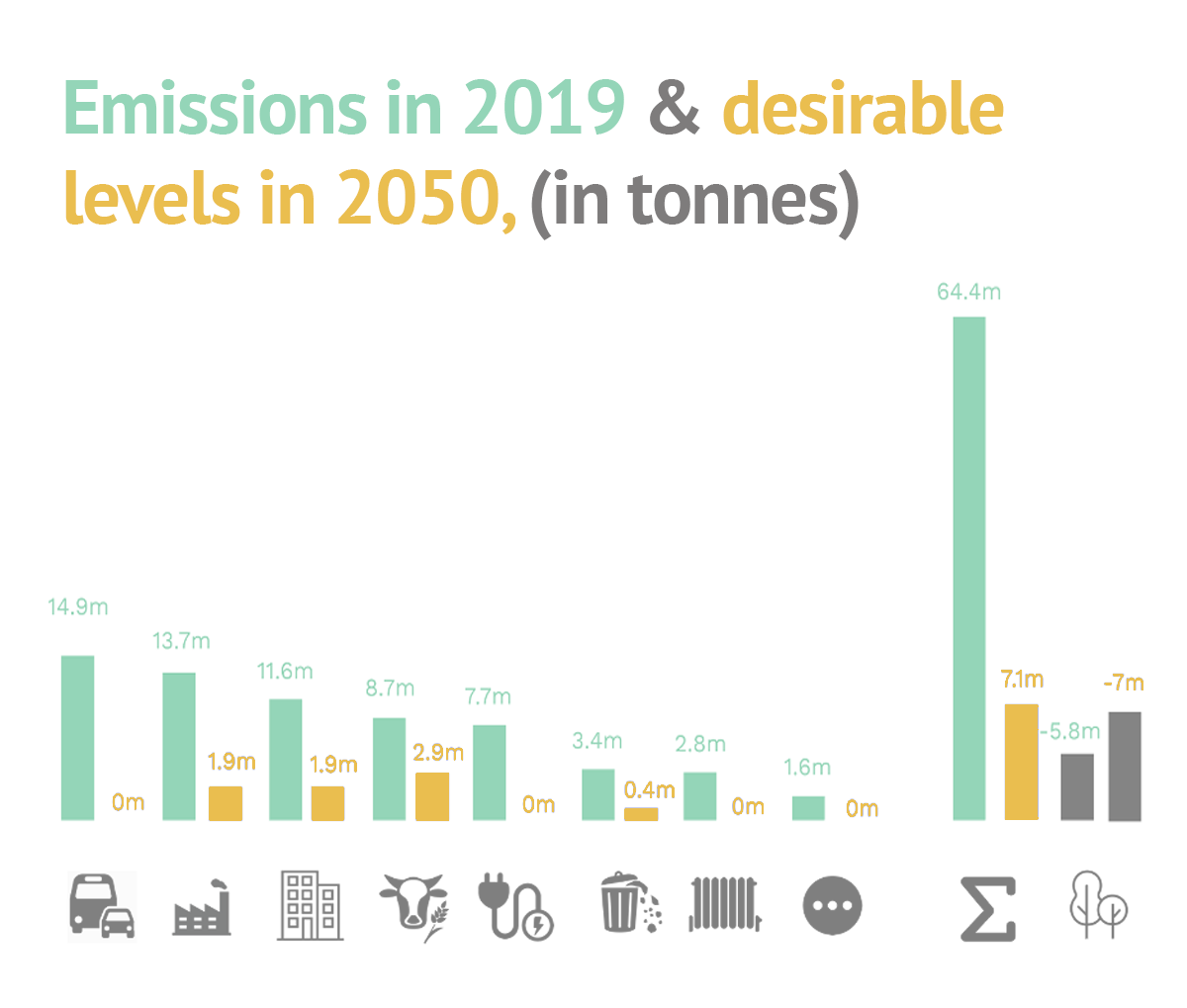

To influence its energy and carbon intensity, in order to reach the neutrality goals, a sectoral approach shows what – in this case Hungary – how these reduction targets can be broken down.

To reach the carbon neutrality goals, a country would have generally two other opportunities (decreasing energy intensity is unlikely): increasing its carbon dioxide absorption or exporting its carbon-intensive activities – although the second option would not help the climate holistically at all.

To influence its energy and carbon intensity, in order to reach the neutrality goals, a sectoral approach shows what – in this case Hungary – how these reduction targets can be broken down.

In order to get to the desired net zero emission level, these reduced emission levels need to be met with increased natural absorption capacities, amounting to 20.000 additional acres of forest annually in the next 30 years.

The journey is quite challenging but not impossible:

during the next 30 years, annually a 2.2-2.4% reduction is needed both in Hungary and in the EU to reach the levels. The key areas for this in Hungary are, as also visible above: transport, industry, building sector, power generation. Systemic challenge will be needed in the transport sector, however: a revolution will need to take place in this field to achieve carbon neutrality. Profound technology change in the CO2 industries and a technology shift in agriculture is required as well. Though today’s technology might be sufficient to take us to these targets, we need to keep in mind, that

further technology revolution is needed to reach the carbon neutrality goals by 2050.

You can watch the event’s recording here:

Századvég Economic Research Institute was established in Budapest in 2010 and is a member of the Századvég Group. As a key player in the domestic advisory market it seeks to support public administration and businesses in the private sector in their policy-making and strategic operations with its knowledge, experience and approach. It has eight business units: digital economy, social research, energy and climate, development policy, education, health, macroeconomics, and the agricultural sector. Századvég’s capacities are complemented by its primary research capacities, which use multiple qualitative and quantitative methodologies, including recent surveying technologies such as social listening or eye tracking analyses.